Cherokee Ed and the Circus That Stayed

I first heard about the “circus that stayed” when I was eleven years old. My sister Frances Browning and I were visiting Anna V. Lesousky, and — bored out of my mind with their company — I got sent off to chat with her father, “Prof. Al” Lesousky. He was in his office, surrounded by papers and books, deep into researching a strange bit of local history: the tale of a circus that rolled into town… and never really left.

It stuck with me.

Later in life, the story would come up from time to time — usually when Daddy or one of the other old-timers mentioned the old Cherokee Ed farm. Just hearing that name made you pause. Who the hell was Cherokee Ed?

The name popped up again in the 1980s, when Joseph Ellert Mudd began documenting local history on video. That’s where I heard Martin Mudd’s version of events — including the unforgettable bit about the lion scaring the livestock every time it let out a roar.

Eventually, I came across Merrill Dowden’s article in the Saint Charles Catholic Church 225th Anniversary publication, which pulled together many of those scattered memories.

And, well… add in the fact that I’ve retired from a few business ventures and finally have time to dig into these kinds of stories — and here we are.

This is what I found.

An October Morning and a Train

Imagine a warm morning in October. Mist still lifts off the rolling Kentucky fields when an unexpected sound echoes through the hills — the distant whistle of a steam locomotive, drawing closer.

Locals pause in their chores. Children perk up their ears. A train is coming — but not the usual freight or passenger line.

This was something extraordinary: a circus train, rumbling toward the tiny depot of Saint Mary. And painted in bright letters along the side of one of those cars were the words:

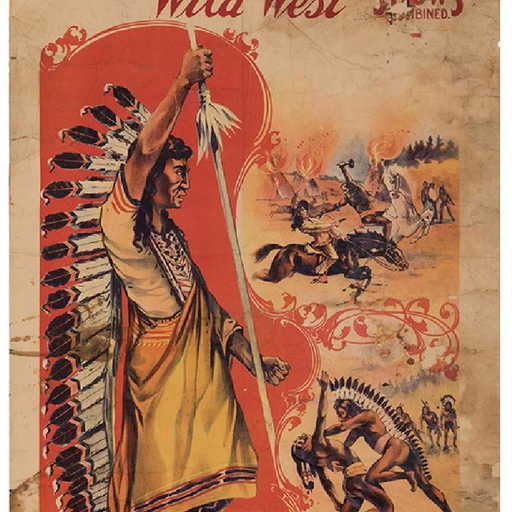

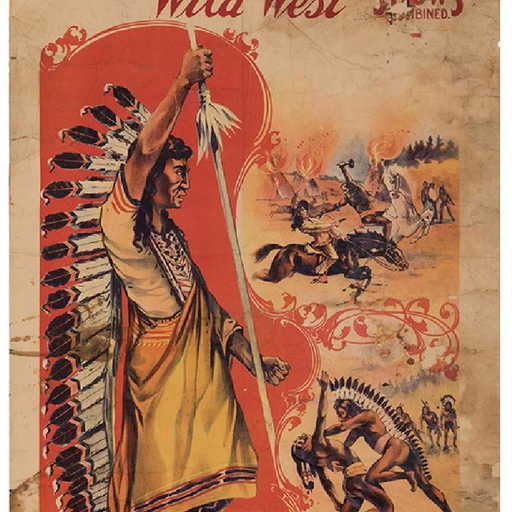

Cherokee Ed’s Wild West and Trained Wild Animal Shows Combined.

Cherokee Ed’s Dream: From Saloon to the Wild West

At the center of this unfolding drama stood Edward “Cherokee Ed” Baumeister, a Louisville saloon keeper with big dreams and a flair for the dramatic. He wasn’t a famed cowboy or seasoned showman. The “Cherokee Ed” nickname was a bit of self-styled bravado — part of a persona he built while pouring drinks and making connections with a colorful crowd of hustlers, gamblers, and showmen.

By 1909, perhaps inspired by Buffalo Bill Cody and other frontier troupes, Ed reinvented himself as a show impresario. He launched his own traveling Wild West production — a blend of cowboy stunts, sharpshooting acts, and exotic animal spectacles designed to thrill small-town America.

He brought in a veteran to help: Col. Clarence Smith, an experienced circus man who had previously worked with Ed on a smaller wild animal exhibition. With Smith managing logistics and Ed fronting the money, the Cherokee Ed Wild West Show prepared to hit the rails.

Wagons from a Circus Graveyard

Running a circus wasn’t cheap, even for a wealthy saloon owner (rumors said Ed was worth nearly a million dollars — a huge sum at the time). He needed tents, wagons, railcars, animal cages — the whole moving infrastructure of a traveling show.

So, Ed turned to William P. Hall, the legendary Missouri horse trader known as the “Horse King of the World.” Hall’s sprawling farm in Lancaster, Missouri had become a kind of circus graveyard, filled with equipment from defunct shows. He had recently bought out the Harris Nickel Plate Circus, among others, and now leased or sold used circus gear to new outfits.

Ed struck a deal. Much of Cherokee Ed’s show rolled out on wagons and flatcars that had already seen other tours, their faded paint and worn boards bearing the scars of earlier adventures. To the folks in Kentucky, though, it was brand-new magic.

A Short-Lived Wild West Adventure (1909)

In 1909, the Cherokee Ed Wild West Show embarked on its inaugural tour. The show traveled by rail with about ten cars — modest compared to the giants like Ringling, but still impressive. It featured cowboys, trick riders, Native American performers, and a menagerie of wild animals.

The Donaldson Lithograph Company of Newport, Kentucky printed the show’s eye-popping posters: galloping horses, rifle-toting women, and staged “Indian attacks,” all meant to stir excitement and sell tickets.

For a brief moment, it looked like Ed’s gamble might pay off.

But the reality of touring was unforgiving. Railroad fees, animal feed, performer wages — costs mounted quickly. And within weeks, trouble struck. As the show reached West Virginia in mid-1909, it was hit by a wave of attachment suits — legal claims from unpaid suppliers.

According to Variety, the show was “almost smothered under a rain of attachment suits.” Equipment was seized. Performers went unpaid. Chaos likely reigned under the tents.

One young man named Floyd King, a popcorn vendor (or “butcher” in circus slang), was among those stranded. He had run off to join the show seeking adventure — and within ten days, the show folded. He returned home to Memphis, broke and embarrassed.

Floyd would go on to become a major figure in American circus history. But he never forgot that first lesson: a circus can collapse overnight.

By the fall of 1909, the Cherokee Ed show limped back to Kentucky, wounded and diminished — but not yet finished.

The Circus Comes to Saint Mary, Kentucky (1910)

Rather than call it quits, Cherokee Ed regrouped for another season in 1910. Whether he paid off debts, found new investors, or got a break on equipment leases from Hall, the show hit the road again.

That’s how Saint Mary, a quiet community in Marion County, became the scene of an unforgettable event.

One fine day, the circus train pulled into the depot and began unloading its spectacle. Many years later, local writer Merrill Dowden would recount the scene in the Courier-Journal, drawing from the vivid memories of Coleman Smock — who, at just eight years old in 1910, had stood wide-eyed at the tracks and watched it all unfold. Smock’s recollections spanned several years, from the thrilling arrival of the show through to 1913, when the last remnants of the circus finally disappeared from Saint Mary.

Car by car, the wagons came down: canvas tents, stock cars of animals, parade wagons. Horses, mules, maybe even longhorn steers snorted at the Kentucky air. There were wild animals, too — a lion or bear pacing restlessly in its cage.

Roustabouts jumped into action, barking orders and hammering stakes. The big top went up, followed by side tents. Dowden wrote that the tents “sprouted like mushrooms” on the field.

By noon, the transformation was complete. Farmers arrived from miles around in wagons. Children climbed fences. Mothers clutched babies. Even seminarians from nearby St. Mary’s College wandered over to see the marvel.

Cherokee Ed himself was there, surely, dressed to impress — broad-brimmed hat, fringed jacket, maybe a cigar clenched in his teeth. He strutted through the grounds, greeting locals with the flair of a seasoned showman.

When the performance began, the band struck up and the big top filled with sound and dust.

Cowboys galloped in, performing dizzying trick rides. Sharpshooters dazzled the crowd — a woman blasting glass balls mid-air, a rifleman snuffing candles with a bullet. The audience gasped at every CRACK of the gun.

There were theatrical skits, too. A mock “Indian attack” unfolded, complete with war whoops, wagon circling, and the heroic rescue by cowboy cavalry — a highly choreographed bit of frontier mythmaking, but to locals, gripping and exotic.

Then came the animals.

A brass fanfare signaled their entrance. Cages rolled in. A lion roared. A trained bear stood on hind legs. Sammy the Turk — a mysterious figure with a heavy mustache and stories no one could confirm — cracked his whip and put the lion through his paces, the big cat snarling and leaping at his commands.

Coleman Smock — the doctor’s boy, just ten years old at the time — would never forget one terrible afternoon when showmanship gave way to horror. Sammy the Turk, perhaps rushing or cutting corners, decided to feed the lions without the usual pitchfork between the bars. Instead, he pushed a slab of meat through with his bare hand. In a flash, the big lion — a male called King Sim — lunged and clamped down. There was a scream, the clatter of a dropped bucket, and chaos as roustabouts scrambled to intervene. Sammy was rushed to the town doctor’s office — Coleman’s own father — his arm shredded and hanging limp. The injury was too severe to save. King Sim had mangled Sammy’s arm so badly it had to be amputated halfway between the elbow and shoulder. Coleman remembered the hush that fell over the camp.

“The Circus That Stayed” – Local Legend and Aftermath

But the story doesn’t end there. Unlike most circuses that packed up and moved on by dawn, this one… didn’t. Something went wrong. Maybe it was poor ticket sales. Maybe debts caught up again. Whatever the cause, the show stopped moving.

By morning, the tents came down. The locomotive steamed off. But some parts of the show remained behind.

People began calling it “the circus that stayed.”

Most famously, a huge wooden animal cage was left on a farm at the edge of town. Maybe it was too heavy to move. Maybe the show couldn’t afford the transport. Either way, it sat there for years — a relic of roaring lions and missed dreams.

Kids dared each other to touch it. They pointed out the deep claw marks in the wood. They told stories about what beast had once prowled behind those bars.

It wasn’t just the cage. Locals say a few animals were left, too — aging horses or mules, maybe a stray circus dog. Some whispered that a leopard or panther was kept briefly in that same cage before being sold off, its cries echoing through the night.

Most of the animals and performers didn’t vanish entirely. Instead, they moved a couple miles out of town to a farm that Cherokee Ed had rented — a quiet patch of land along what is now called Wimsatt Road. There, behind split-rail fences and rows of cedar, life limped on in the aftermath of the show. For a time, the Wild West lived in miniature on Kentucky farmland.

Martin Mudd, who was growing up a mile or so away, remembered: “When that lion roared, it spooked the cattle and other livestock to no end!” His family’s animals would bolt or bellow, panicked by the sudden sound of Africa echoing across the fields of Marion County.

Cherokee Ed — or someone from his crew — lingered. The property became known as “Cherokee Ed’s farm.” Tommy Lee Mattingly, longtime postmaster of Saint Mary’s, remembered exploring it as a boy: rusted wagon wheels, scraps of canvas, the scent of old sawdust still clinging to the earth. He later confirmed the stories told by Coleman Smock to newspaper writer Merrill Dowden, helping preserve the legend for future generations.

To him and his friends, it was like stumbling onto a pirate shipwreck — only this one had lions and sharpshooters instead of treasure maps.

Legacy of a Dream

Edward Baumeister faded from show business not long after. The Wild West was already on its way out. Vaudeville, movies, and the electric age were taking center stage.

But in Marion County, his name lived on.

In 2010, the St. Charles Catholic Church 225th Anniversary reprinted Merrill Dowden’s article. Locals still remembered the day the circus came — and never quite left.

The tale of Cherokee Ed’s Wild West Show is now part of Kentucky folklore. A story of big dreams, dusty roads, and a cage that wouldn’t budge. Fact and legend blurred like the mist over those June fields.

And somewhere out there, deep in the woods, maybe the bones of an old wagon still rest in the soil.